ToK Essay Titles May 2023 Prompt 1

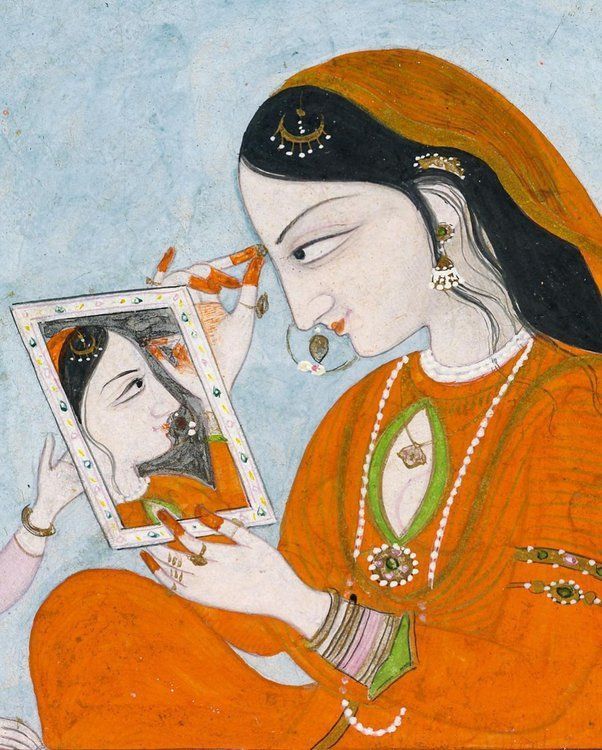

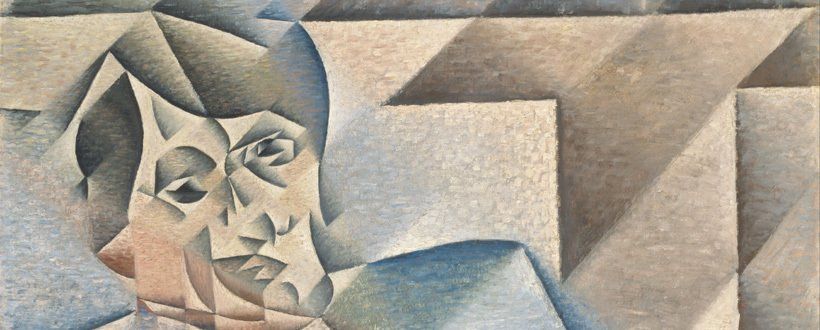

Artistic replication & the power of influence

Read this:

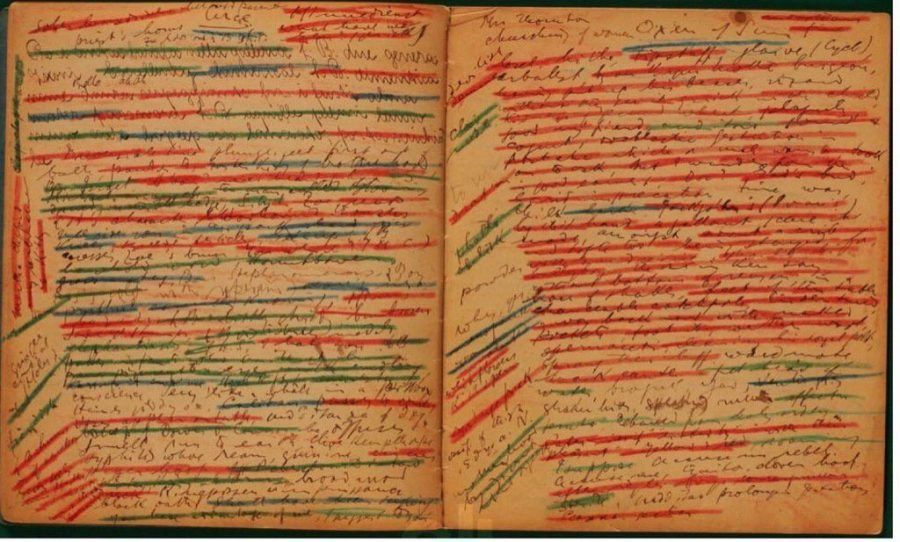

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.

Sir Tristram, violer d’amores, fr’over the short sea, had passencore rearrived from North Armorica on this side the scraggy isthmus of Europe Minor to wielderfi ght his penisolate war: nor had topsawyer’s rocks by the stream Oconee exaggerated themselse to Laurens County’s gorgios while they went doublin their mumper all the time: nor avoice from afi re bellowsed mishe mishe to tauftauf thuartpeatrick…

Now this:

"What's it going to be then, eh?" There was me, that is Alex, and my three droogs, that is Pete, Georgie, and Dim. Dim being really dim, and we sat in the Korova Milkbar making up our rassoodocks what to do with the evening, a flip dark chill winter bastard though dry. The Korova Milkbar was a milk-plus mesto, and you may, O my brothers, have forgotten what these mestos were like, things changing so skorry these days and everybody very quick to forget, newspapers not being read much neither. Well, what they sold there was milk plus something else…

Both extracts seem somewhat ‘out there’ – the first passage perhaps more than the second. Both are the first 10 lines of stories that caused controversy at the time of publication and beyond. The first passage comes from Finnegan’s Wake, by James Joyce. The second passage is from A Clockwork Orange, by Anthony Burgess.

The reason for the comparison? The idea of ‘literary influence’. How one artist’s feeling for words and expression is shaped by another’s as part of a process of finding one’s ‘voice’, ‘identity’ or ‘persona’.

Very often artists achieve this by means of ‘pastiche’: copying the idioms, tone and phraseology of the writers they admire until they evolve a textual self with which they produce their stories. It’s pretty much how all of us actually learn things during our lives. We copy those around us, especially our family members and eventually our peers and celebrities and ‘influencers’!

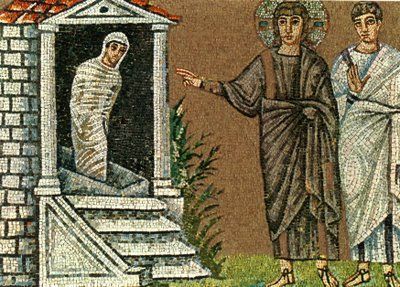

This form of ‘copying’ is the broad sense of the term ‘replicability’ in this Title. From one point of view, such ‘replication’ leads to the creation of original works of art which make us see the world anew. From another point of view entirely, such copying borderlines on artistic plagiarism, fraud or forgery.

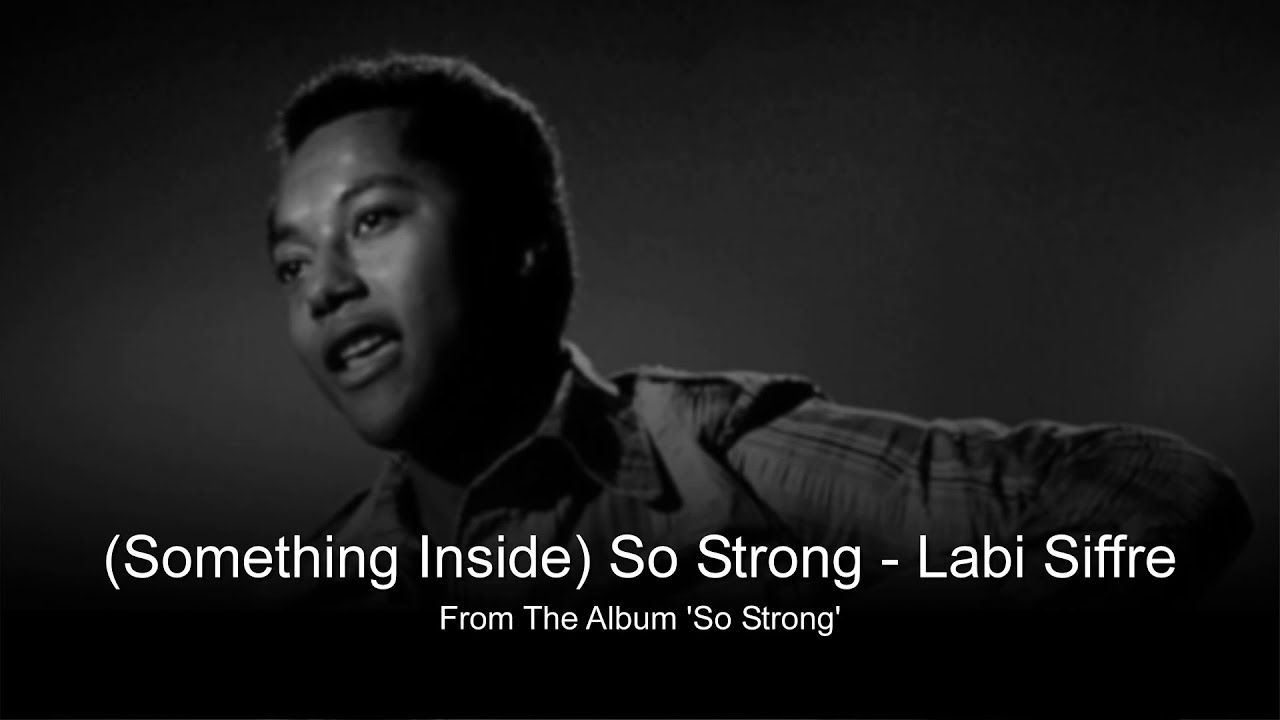

The ethical dimension of such fraudulent copying can also be viewed from two perspectives. On the one hand, you may have heard of recent cases in which musicians have been accused of ‘stealing’ musical riffs wholesale from one artist and using them in their own songs (Ed Sheeran). You may also know about painters who copy the masters as part of a heist to replace an original with a forgery. On the one hand, forging art works as an ironic ruse to undermine arrogance and evil seems almost justified – this is the story of ‘The Last Vermeer’ about an artist who ‘stole’ art from the Nazis without them ever realising it…