ToK Essay Titles May 2023 Prompt 5

Technology & visualising the brain

Sometimes mental health clinicians have a poor reputation for communicating knowledge. Even though we expect experts to be trained in listening carefully and talking to us on a human level. It’s understandable, since much of the time the knowledge shared isn’t always good news: a personality disorder, an addiction that seems irreversible, an invasive test. The list goes on.

However, as part of a medical, and ethical, obligation to inform a patient about the nature of an ailment and a course of remedy, clinicians need to communicate clearly the possible causes for, and potential consequences of, a health problem.

Consider physiological problems with the brain, such as memory loss. One of the first things a medical expert will do is recommend a brain scan. Technological improvements have led to the development of a range of digital tools to help doctors measure brain states as part of building a picture – a map – of brain activity.

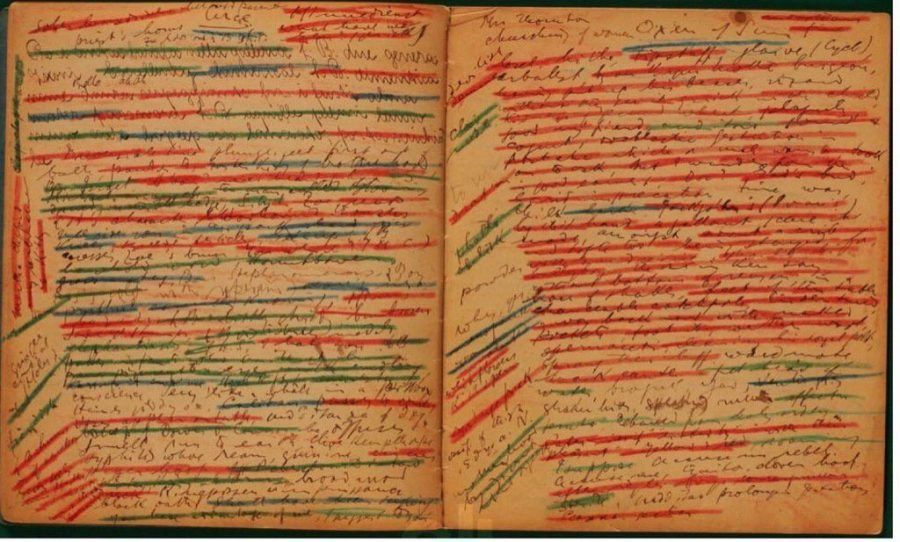

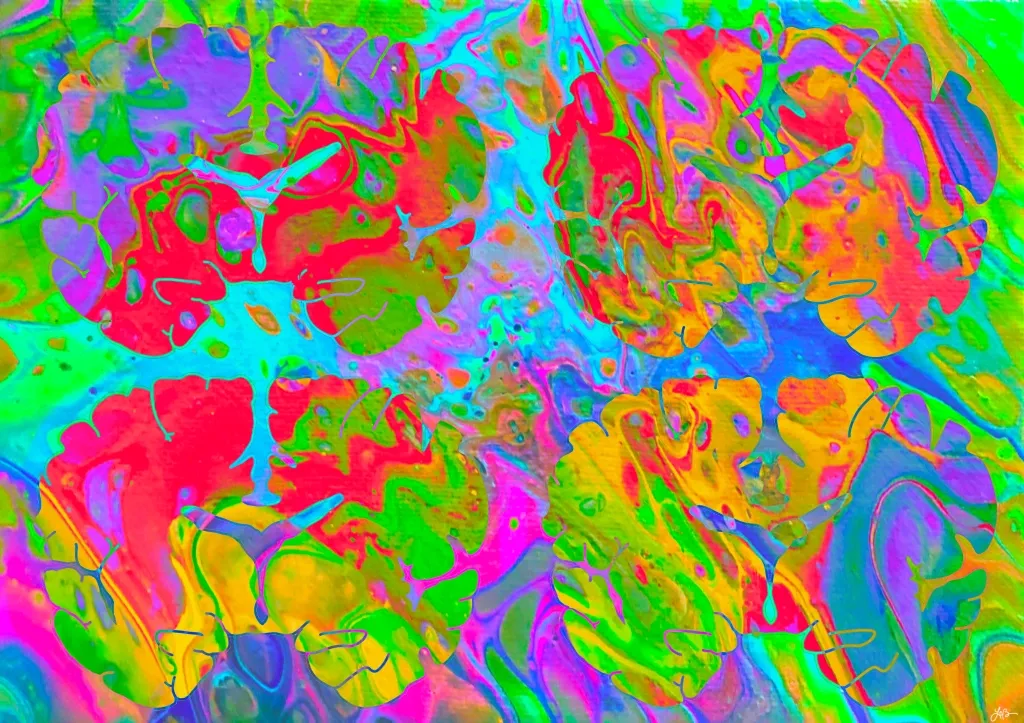

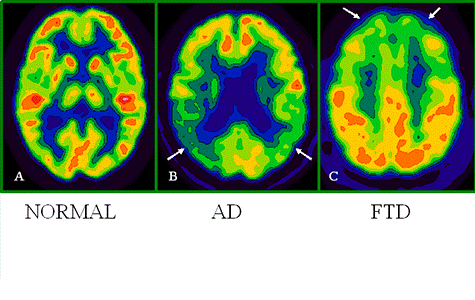

PET (Positron Emission Tomography) imagining – sounds like something from Star Trek – is one such tool that enables specialists not only to clarify a diagnosis, but also to communicate and explain to patients and other clinicians what is going on inside the brain. While the technicalities of how PET scans work isn’t so important here, their role as part of the scientific method is significant. First, the tool helps generate observable evidence which can help confirm or refute a particular diagnosis. Second, the photographic representation can be used to highlight similarities and differences between ‘normal’ or healthy brain activity and ‘abnormal’. Finally, even though the images must be interpreted, which brings a subjective element into the scientific process, and can lead to judgement errors, they provide a baseline of ‘evidence’ which can be examined by other experts as part of acquiring ‘second opinions’ on the nature of the symptoms displayed by a patient.

Consider the following images:

Even if there is no obvious or ready treatment for extreme cases like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or the Frontotemporal dementia (FTD), the visual representations are helpful in allowing both experts and lay people to make sense of specific health conditions.

The implications of this viewpoint are significant: when we’re at our most vulnerable, a clear communication about our health, supplemented by a visual image, can give us some element of control over ourselves and the future. This complementary process acknowledges our agency at a time when we feel helpless and makes a part of any decision-making process. And, if nothing else or even if we’re left with more unknowns, it sustains a hope in the people who are doing their best to help us in a moment of need.