ToK Essay Titles May 2021 Prompt 2

ToKTutor • 11 October 2020

History, endtimes and moral progress

One way to differentiate between ‘change’ and ‘progress’ is to think of whether or not a change in knowledge is goal orientated. For example, when Fleming discovered penicillin, scientists would eventually talk of Fleming’s breakthrough as real ‘medical progress’. This is because it is one of the goals of the medical sciences to save as many lives as possible without harming others or the environment in the process. Even when a goal, such as this one, isn’t entirely pragmatic, we can still point to ‘progress’. Consider the recent developments in theoretical physics at institutions like CERNE. The scientific community’s knowledge of fundamental particles which make up the Universe may have little practical value (for now), but there has still been progress in this field of research.

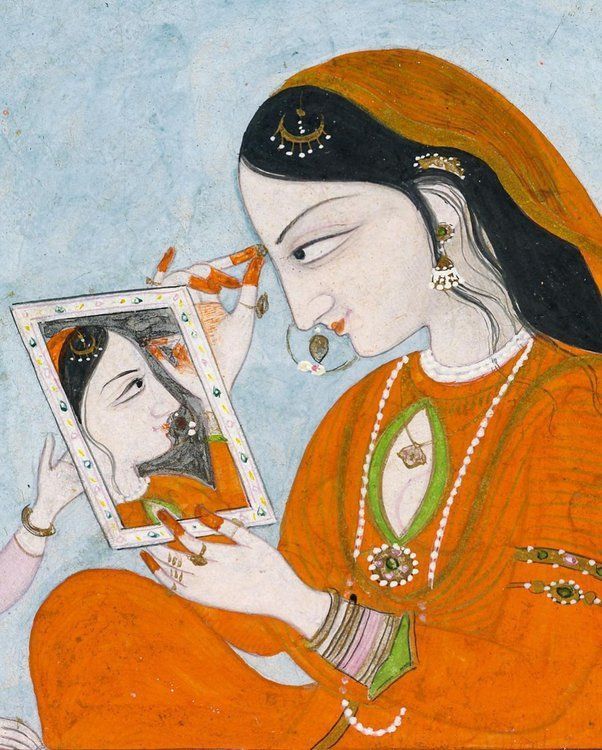

There is a parallel in the Arts. Some Arts are goal oriented in a practical way: they aim to change people’s perspectives by teaching them about the world and its ways. For example, Titus Kaphar’s paintings engage in a ‘truth telling’ project to help us remember the lives of unseen, marginalised people from the past, who lived in the era of slavery and discrimination in the United States. The goal here is to foster tolerance of difference and, as with Fleming, time will tell if Kaphar’s aesthetic innovations will be classed as ‘progressive’. Other artists pursue art for its own sake – for the joy and beauty of making art. This leads to different kinds of formalist genres where technical skill overshadows any content or message the art might have. Examples abound: from Jackson Pollock’s ‘drip’ paintings to John Cage’s ‘silent’ piece, 4’33’’. While these changes in approaches to artistic composition might not immediately affect how WHOLE communities of artist work, they nevertheless mark a more personal progress in the artistic careers of the artists themselves.

In RKS, this line of thinking can be explored in different ways. For instance, the break from the Roman Catholic Church initiated by Martin Luther’s 95 Theses, was certainly a dramatic change but was it ‘progress’? Yes, if you consider that one of Luther’s goals was to make religious faith (and the benefits that went with it, like education) more accessible and personal to the poor masses, rather than a haven for the rich and privileged. On another level, within the Christian framework of sin and redemption, a person’s ‘moral progress’ can be measured in terms of how she aligns her individual will to God’s Will. God’s Will is a good in itself, emanating from his nature as omnibenevolent, and allows one to measure the changes in one’s life towards the ultimate test of one’s moral progress: whether or not one gains access to heaven in the after-life. At least, two problems remain. First, how do we KNOW what God’s Will is for us? Religious experts can help here. And second, is the threat of not getting into heaven strong enough to make us progress morally in this life? A question to address in another post! So far, we’ve been discussing ‘personal’ moral progress. What about the moral progress of the group?

The term ‘eschatological’

can be of help in this context. In specifically Christian terms, ‘eschatology’ describes beliefs about the end of history and the final destiny of human kind. The world we live in is imperfect, so the story goes. God’s final judgement is to destroy the old order and bring humanity into a new order in the afterlife. Religious or moral progress for mankind is defined by our ability to withstand the tribulations of history until the moment of Apocalypse. However, thinkers distinguish between ‘historical’ and ‘mythical’ eschatology to allow for exploration of stories about the end of the world which don’t belong to this traditional Christian framework of thought. These two approaches imply different conceptions of TIME. In a primarily historical eschatology, time is thought of in linear terms as progressing from a starting point to an end point within the same continuum; from disorder and chaos to order and harmony. In a mythical eschatology, time is more cyclical in which the ‘endtime’ repeats or returns to the original state of order and harmony in which mankind lived. Both storytelling frameworks allow an equally interesting way of differentiating between change and progress of individuals and groups in the context of morality…