ToK Prescribed Essays November 2020 Titles 3 & 5 Part 2

ToKTutor • 2 May 2020

‘Novum Organum’ vs ‘Spiritual Diaries’: The Light and Dark Twins

Both Dee and Bacon were driven by a key assumption shared by the intellects of the time: an undying faith that the universe was not random. They believed that behind the suffering and misery and shortness of life, there was an order just waiting to be known. Man was central to this enterprise and as such not only as ‘the most important thing in the universe’, but also as the pivot around which this knowledge ‘revolves’. Bacon’s faith was in humanity’s enduring capacity to know nature and thereby control all aspects of it, the social, economic and political, which laid the path for the innovations of the Industrial Revolution in the 18th Century. Dee’s faith was in bringing to birth a new order into the world grounded in divine principles but with humanity as the driving force of this movement. Some historians argue that this is how Queen Elizabeth used Dee's knowledge to justify her own imperial ambitions and pave the way for the later Colonial dominance of the English.

The difference between them lies in the fact that while Bacon saw the problems of this assumption, Dee did not appear to do so. Bacon saw the problem of human blind spots when it came to applying the principles of science effectively. What today we call the central ‘biases’ that undermine our ability to gain or produce knowledge originate in Bacon’s thinking about the ‘Idols of the Mind’. Bacon’s method allowed the possibility of human error, assumptions and prejudice. He understood that future scientists would take his ‘principles’ and resolve their problems to adapt them to new environments.

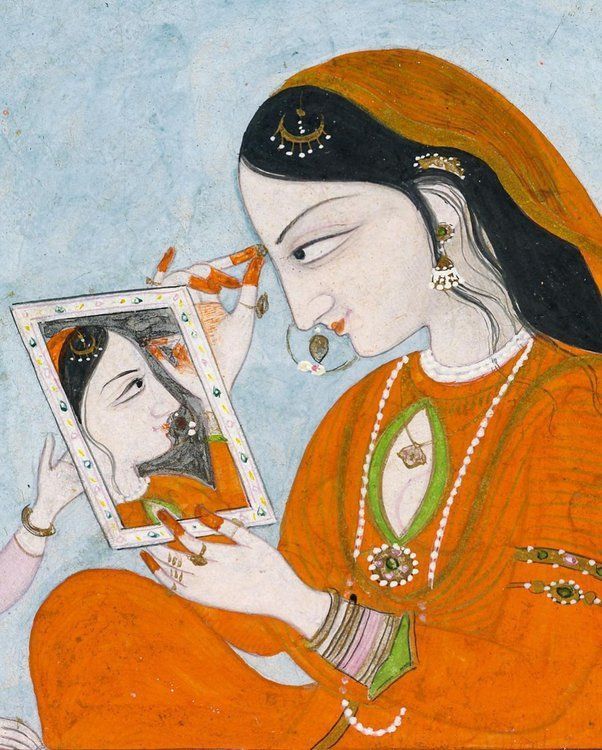

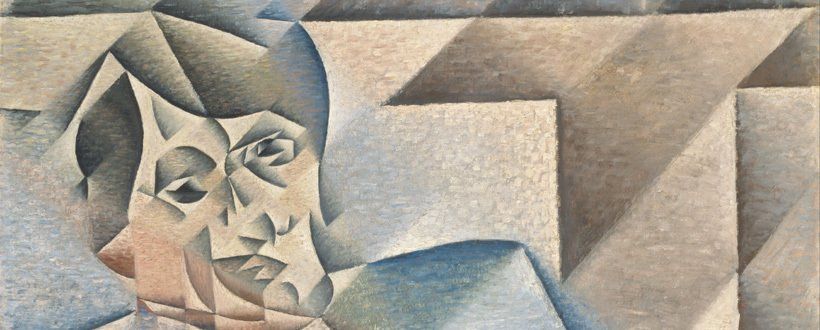

Dee, for all his scientific thinking and knowledge, is an almost forgotten exponent of scientific questioning. Perhaps his over-reliance on magic, obsolete tech and theatre undermined his pursuit of new knowledge, because it was delivered as an ‘absolute truth’ with no further questioning allowed. For a time, nevertheless, it was popular at court and he became a personal consultant to Queen Elizabeth. His shiny, black ‘scrying glass’

exists, however, in the British Museum. It encapsulates the origin story of how too much knowledge came to revolve around us and the problems this can cause. When you look at the surface of the glass, all it seems to do is reflect back a shadow silhouette of yourself. Rather than being a portal to another world of knowledge, perhaps it is also somehow a metaphor for our own blinkered approach to how we come to know what we know…