ToK Essay Titles May 2020 Prompts 2 & 4 Pt 1

ToKTutor • 6 October 2019

Making the strange familiar: Part 1

While a description of something can be made both factually and figuratively, usually only a factual description is seen as being helpful in making explanations of things. Figurative descriptions are often seen to be ‘messy’ and get in the way of giving clear and objective reasons as to how and why things are as they are. But look at this…

Question: What do the expressions ‘iron horse’, ‘floating mountains’ and ‘flying saucers’ have in common?

Answer: They are part of a description or story told in response to something seen for the first time – an attempt to explain or make sense of something unfamiliar and unknown and never experienced before.

The ‘iron horse’ was, allegedly, how a Native North American Indian described the first train that was seen moving across the North American plains. A ‘floating mountain’ (Section: ‘Spanish Contact’) was, supposedly, how the native South American Indian spies described the oncoming ships of the Spanish invaders. And, ‘flying saucer’, as everyone may know, is how the Western media first publicised the phenomenon of UFOs. Now, imagine how each of these assertions were received by the general population: with understanding nods of approval and general acceptance? With undoubting certitude and unquestioning acknowledgement? Nope. Most probably with a lot of hilarity and not merely a pinch of condescending irony.

So you see, the implied distinction between ‘description’ and ‘explanation’ is not always so clear cut and the above examples evidently counter the title quote, especially as regards building new knowledge.

In short, figurative descriptions give us flexibility in making sense of the world, especially when trying to explain to ourselves strange, new experiences for which we struggle to find the right words with which to express them.

Justifications go further than explanations because they require us to align our reasons for why we claim to know what we know with a body of physical evidence that supports those reasons.

However, there is a problem. Some skeptics reject a knowledge claim, not simply on the grounds that it is asserted without evidence, but because the evidence presented is framed in highly analogical terms and is thereby somehow diluted as far as justification of knowledge is concerned. In other words, evidence presented in the form of figurative language is not the best vehicle for justifying knowledge.

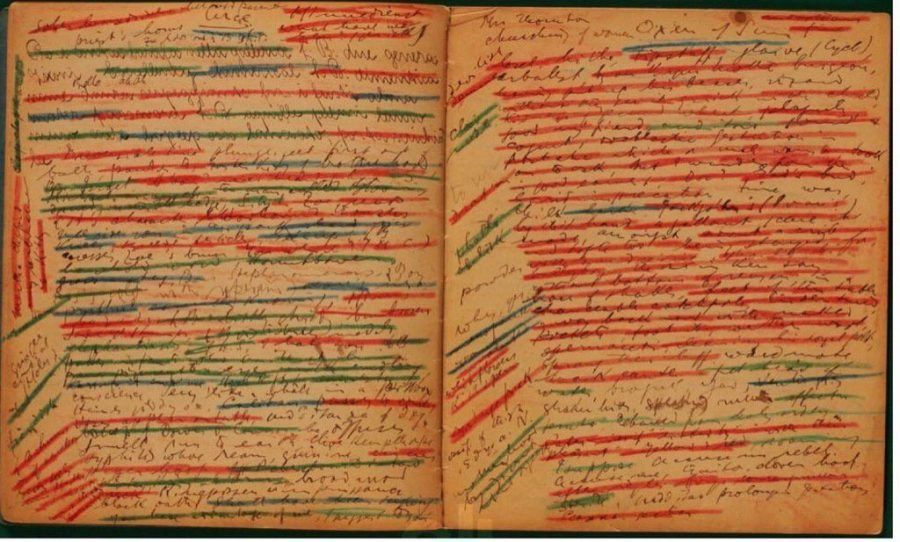

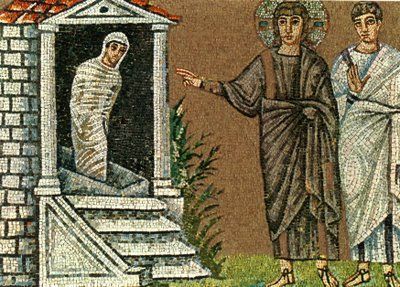

When justifying knowledge claims in the Bible, believers often argue that we shouldn’t take the words of the Biblical stories too literally, because this detracts from their symbolic message or teaching. However, atheists sometimes argue that after you’ve stripped the metaphor away from the language of the stories, there’s nothing of factual substance left in the message which we could reasonably argue represents knowledge. These alternative arguments support not only the idea that there is a ‘sharp line’ between description and explanation (Title 2), but also that analogy aids understanding but not justification (Title 4).

See the next post to think through the idea…