ToK Essay Titles May 2020 Prompts 2 & 4 Pt 2

ToKTutor • 6 October 2019

Making the strange familiar: Part 2

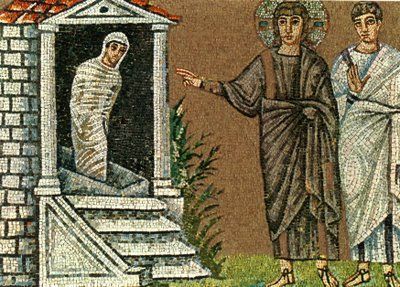

Consider the language of the stories of the Bible, for example. Can we confidently argue that the descriptions and analogies help both to explain and justify knowledge?

On the one hand, believers argue the story of the flood must have been based on true events as we find similar stories in other religious texts. The flood was a significantly catastrophic event throughout the earth to have compelled the imaginations of humans strongly enough for them to have recorded it. Thus sacred texts are seen also to be historical documents in part; primary sources to help reconstruct a historical narrative of the past. And in fact, this is how ‘geomythologists’ use such descriptions or analogies to explain key geological events. In this way, descriptions or stories are used to ‘validate’ if not fully ‘justify’ knowledge which can’t be done by existing scientific approaches. However, when a similar line of argument is made to support the idea that according to the timeline of biblical events, the earth is only 4000 years old, are we to take this literally?

On the other hand, atheists argue that the story of Noah is only that – a story, a fiction. It might be very entertaining and engage us imaginatively and emotionally into a completely different world from our own. Furthermore, we can take whatever moral we want from the story, such as ‘the endurance of human hope in the face of adversity’, but this does not make the events of the story real or true historical knowledge. However, such arguments often detract from the sense that such Biblical myths helped our ancestors to make sense of a random universe and gave them an emotional strength to survive disasters.

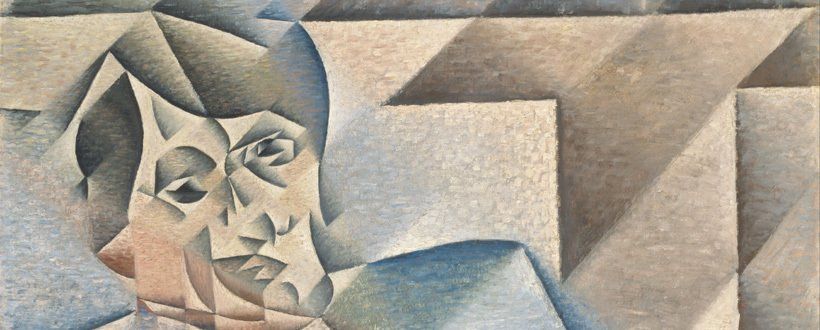

Let’s come round to the previous post again. What do you notice about each of the expressions: ‘iron horse’, ‘floating mountains’ and ‘flying saucers’? They are deeply metaphoric. Metaphor or storytelling, it seems, is crucial to our ability to make sense of the world (understanding), especially our experiences of it. Metaphor fills the gaps, so to speak, in our more literal & factual attempts to grasp order and meaning in what we see in our universe. The North American Indian, seeing a giant, metallic object, racing towards him, breathing smoke and screaming violently, can only grasp what he’s sensing by comparing this unbelievably strange experience in terms of something more familiar to him. Analogy or metaphor helps to suspend our incredulity about the world and reach for knowledge and understanding that slips through our more literal/factual (rational?) approaches.

Which begs the KQ: to what extent is imagination an integral part of building knowledge? Or the more ethical KQ: should knowledge, grasped imaginatively and presented in metaphorical stories, be rejected with a corresponding rejection of the knowledge?

If the South American Indians had collectively accepted the ‘floating horses’ hypothesis, might they have taken more seriously the threat of the invading Spanish ships? A ‘what if?’ question, the answer to which we’ll never be able to know.

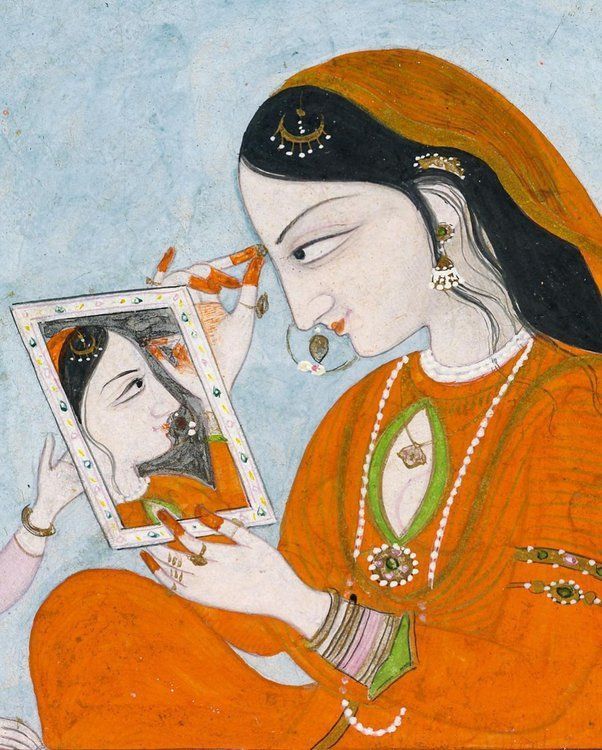

On another level, what happens when we can’t tell the difference between our fictions and the reality from which they are made? What if we believe a fiction to be true...?