ToK Essay Titles Nov 2019 Prompt 4

ToKTutor • 24 June 2019

Kekule's dream and Pasternak's sketches

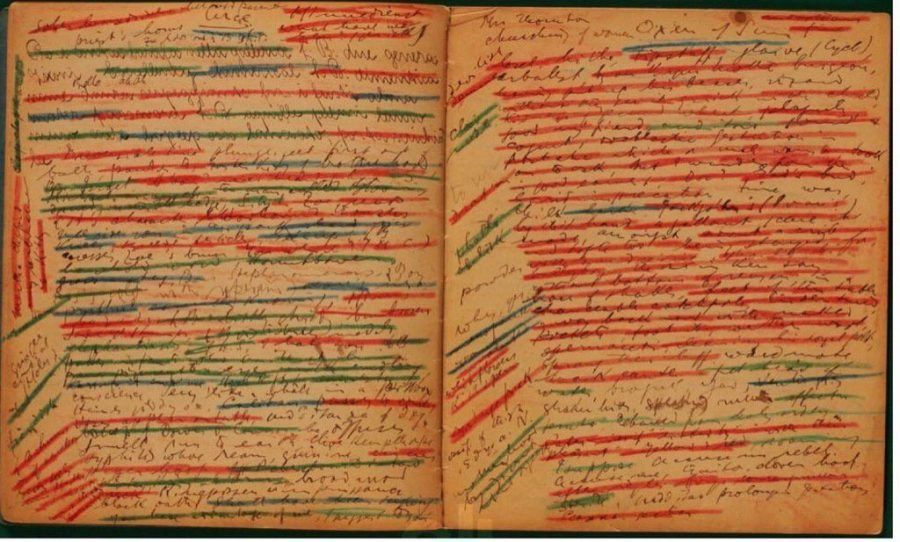

Imagine the scenario. A young Kekulé travelling on a bus and suddenly enchanted by atoms dancing before his eyesight. Later that night he spends the hours sketching the images from his daydream. This is the backstory of his later, more famous, ‘ourobouros’ dream which formed the basis of his discovery of the structure of the benzene molecule. It’s a story that has become the stuff of myth and the example itself is quite clichéd. Still, both experiences have in common the process of serendipity that is sometimes part of the knowledge production process. However, it isn’t as simple as observing then writing down the observations.

In an 1890 lecture, in which Kekule recounted these episodes, he was keen to invite his colleagues to ‘dream’ as part of the scientific search for truth. Nevertheless, he was careful to assert that simply writing down or publishing these dreams without testing them through ‘waking understanding’ is futile. In other words, the kind of insight that emerges from such accidental moments of lucidity is just the start of the knowledge making process, not the end. We don’t have ready-made knowledge through simple observation. We have, in the sciences at least, to scrutinise the observations, test them according to a rigorous process of experimentation and reasoning and prediction. Once the initial observations have been filtered through the scientific method, we can write up our theory and present it to the wider community for peer review.

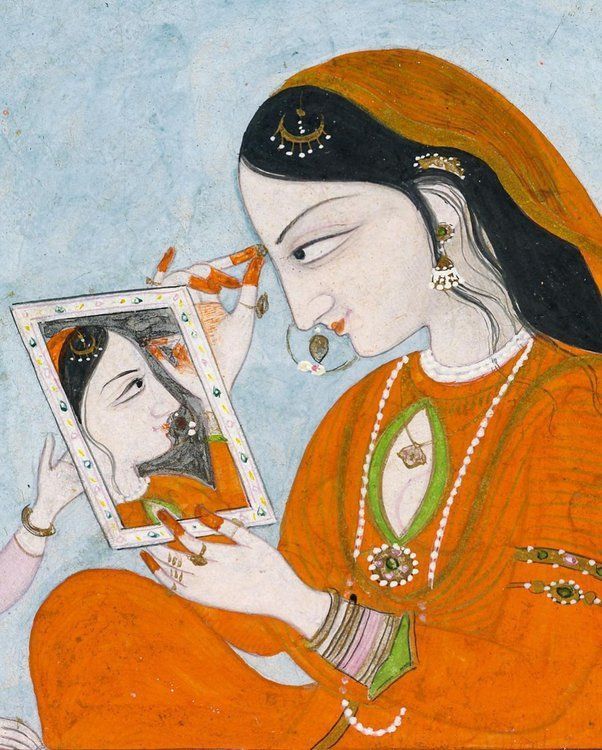

The arts, on the other hand, are all about observation in the broadest sense of encompassing all five senses. Consider the ‘lightning sketches’ of the post-impressionist painter, Leonid Pasternak. Like the phone carrying, photo snapping general public of today, he would always have his art materials to hand, so that he could capture an experience in a particular time and place in all its immediacy of the moment. Just like our need to encapsulate a memory in a visual form, Pasternak’s sketches achieve the same purpose, though realism in representing reality was not his ultimate aim.

So what’s the difference between him and us? Pasternak’s daughter, Lydia, recalls how “observing and drawing were for him a natural necessity, like sleeping and breathing…”, suggesting how an expert artist’s trained eye is somehow compelled to see the world and, in the very depiction of it, whether through writing or drawing or any other medium of expression, to filter that world through his own perspective. Of course, this changes the world; it becomes transformed in the art work and is coloured by the emotions and biases of the artist. This is inevitable and, to some extent, desirable. Why? Because one test of the quality of an artwork and the knowledge of life it represents to its audience is that to enter the world of the art demands an imaginative effort, during which we must temporarily place aside any questions or doubts we may have about it. Another test is that once we leave the world of the art and return to our own day to day world, we see things differently. Through our engagement with the art, our own perspectives will have been changed forever…