ToK Essay Titles Nov 2019 Prompt 5

ToKTutor • 8 July 2019

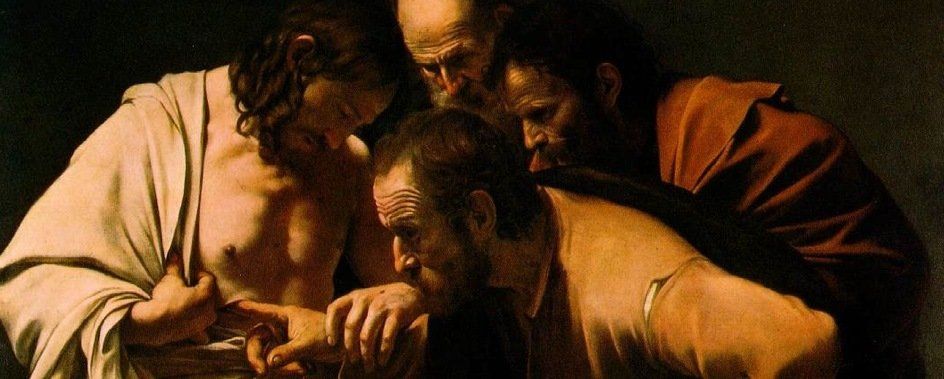

Doubting Thomas, scepticism & knowledge

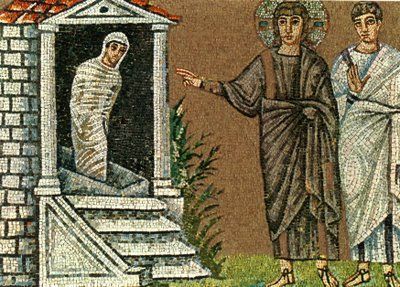

Jesus was by all accounts an extraordinary being. Extraordinary things happened to him, nothing more so than his resurrection after being crucified. Hence, when news of this amazing event reached his ears, Thomas, one of Jesus’s disciples, responded like a modern day sceptic: “unless I shall see in His hands the imprint of the nails, and put my fingers into the place of the nails, and put my hand into His side, I will not believe” (John, 20:24-9). In spite of witnessing Jesus do some pretty wild things while he was still alive, like bringing Lazarus back from the dead, this strangely morbid request for concrete, physical evidence seems out of place.

The incident has generated much debate as to the meaning of Thomas’s reaction. Didn’t he already believe in the divinity of Jesus? Why should he question his faith? In the alleged words of Carl Sagan, what Thomas wanted was some ‘extraordinary evidence’ to support an ‘extraordinary claim’. That is, Thomas was not going to accept the claim about resurrection simply through eye witness testimony. He wanted first-hand experience of seeing the nail holes and feeling the wounds in Jesus’s body.

Caravaggio’s painting gruesomely depicts how Thomas got what he asked for and, at the same time, imagines that he probably got more than he bargained for! The impact on Thomas was, nevertheless, instantaneous. He believed. His knowledge and faith now reinforced, Thomas’s life took on new meaning and purpose. He became the Apostle who took the teachings of Jesus into the East and founded the Christian mission in India.

But what about us? Isn’t Thomas supposed to be the perfect TOK role model: the one who questions knowledge claims? Aren’t we supposed, like Thomas himself, to question the reliability of eye witness testimony and not take things on the basis of personal anecdotes? The problem is, of course, that Thomas had the privilege of coming face to face with the resurrected Jesus. All we have is a third party story by John which recounts Thomas’s own discovery of extraordinary evidence of Jesus’s resurrection. We don’t have access to this or any other such concreted evidence. So shouldn’t we remain true to the spirit and letter of Thomas’s own scepticism? From a religious perspective, probably ‘No’.

God’s response to Thomas gives a clue as to why we should remain open to the possibility of the extraordinary without requesting extraordinary concrete supporting evidence: “Because you have seen me, have you believed? Blessed are they who did not see, and yet believed.” One interpretation of these words is that we must embrace the possibility that we will never get the kind of hard physical evidence that Thomas received in our quest to know Christ. This means that in some ways Christ is never fully knowable and will remain a mystery. In other words, Thomas’s own doubts become a permanent symbol of the divine mystery of God’s creation and all the associated wonders of His work. What remains is for us to bridge that doubt and uncertainty by opening ourselves up to faith

as a justification of religious knowledge.

The Christian Scriptures point to two sense of ‘faith’ that encapsulate this idea. First, faith is described as ‘a conviction of things not seen’ (Hebrews, 11:1). That is, believing something without grounding it in the evidence of the senses. Second, ‘faith apart from works is dead’ (James, 2:26). That is, believing is not simply an intellectual acknowledgement of, or justification for, something more than human; it is a commitment to act on your beliefs. Initially, Thomas may not have had faith in the first sense, but he more than made up for it by showing faith in the second sense. In short, his immediate scepticism neither diminished, nor undermined, nor jeopardised his later successful production of Christian knowledge through his missionary work in the Eastern lands…